Released in 2006, Half Nelson quickly established itself as a pivotal work in indie cinema, casting a critical lens on the intersection of addiction, race relations, and the student-teacher dynamic in the United States’ urban school system. Directed by Ryan Fleck and written by Fleck and Anna Boden, the film set itself apart through its raw, unflinching portrayal of the internal battles fought by its protagonist, Dan Dunne. Played with startling intensity by Ryan Gosling, Dunne is a middle school history teacher who faces the Sisyphean task of educating students while privately succumbing to his own addiction to drugs. Gosling’s performance, a career-defining moment, garnered widespread critical acclaim and earned him his first Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. At the heart of Half Nelson lies an emotional undercurrent fueled by the relationship between Dan and one of his students, Drey, played by Shareeka Epps. Their bond offers a poignant examination of redemption, connection, and the messy complexity of human frailty.

Dan Dunne: The Anatomy of a Flawed Hero

At first glance, Dan Dunne seems like the antithesis of a conventional hero. He is not the archetypal inspiring teacher whose sheer passion and charisma turn around the lives of his students, nor is he an entirely lost soul resigned to a life of hopelessness. Instead, he straddles a line between both worlds, offering his students provocative lessons on history and social justice while privately struggling with the crushing weight of his drug addiction. His behavior veers between functional professionalism and self-destructive collapse, marking him as a deeply flawed, deeply human character.

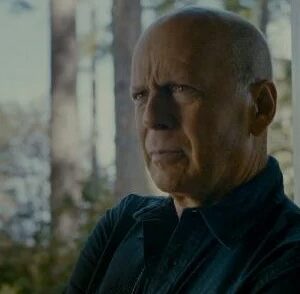

Ryan Gosling’s portrayal of Dan is nothing short of mesmerizing. In one moment, we see him as an articulate, charismatic teacher whose unconventional approach to history opens the minds of his students. The next, he spirals into moments of vulnerability, fighting a losing battle with addiction. Gosling taps into the paradoxical nature of Dan’s existence—the simultaneous ability to inspire and the overwhelming inability to save himself. This portrayal is not just a role for Gosling, but a metamorphosis that signals his evolution as an actor capable of grappling with roles of immense moral and emotional ambiguity.

Dan’s addiction is not presented with the glamor or sensationalism often associated with Hollywood’s depictions of drug use. Half Nelson avoids melodrama, choosing instead a stark and realistic portrayal that shows addiction as a daily, grinding battle—a disease that eats away at personal relationships and professional responsibilities alike. His drug use is never romanticized, nor is it neatly explained away with traumatic backstory or a moment of revelation. It simply is, much like his presence in the classroom—a fact of his life that both defines and diminishes him. He is not trying to escape, nor is he actively seeking redemption. Instead, he exists in a constant state of turmoil, his life unraveling quietly, one bad decision at a time.

The Student-Teacher Bond: A Complex Relationship with Redemption

One of the most significant and deeply affecting relationships in Half Nelson is the one Dan forms with his student Drey. Drey, a young girl from a troubled background, is at a crossroads in her life. Like Dan, she exists in a world fraught with instability and looming danger, caught between the pull of drug dealers in her neighborhood and her desire for something better. It is a relationship that starts with a simple discovery—Drey finds Dan using drugs after class one day—and develops into a connection that defies easy categorization.

The bond between Dan and Drey is neither simple nor straightforward. On the surface, it might seem like a classic student-teacher dynamic where the wise mentor helps the struggling youth navigate life’s hardships. But Half Nelson subverts this expectation. Dan, deeply flawed and barely able to manage his own life, is hardly a conventional role model. Yet, in Drey, he finds a mirror to his own internal conflicts, and Drey, in turn, sees in Dan a figure who straddles the same moral ambiguities that define her own world. They are both seeking escape, both standing on the precipice of choices that could either ruin or save them. In their shared moments, there is an unspoken recognition of their vulnerabilities—a recognition that provides the emotional depth of the film.

As the film progresses, Drey is drawn into the world of drug dealing through her relationship with Frank (Anthony Mackie), a local dealer with whom she has familial ties. Dan, seeing Drey’s involvement with Frank, attempts to steer her away from this life—yet he is no moral authority. His own addiction undermines his credibility, and in some ways, Dan’s concern for Drey is also a form of self-repair, a way of doing for her what he cannot do for himself. Their relationship becomes a powerful exploration of how human connections can simultaneously offer the potential for salvation while also complicating the path to redemption. Dan’s failure to save himself is juxtaposed with his hope for Drey’s future, creating a poignant tension that drives the film’s emotional core.

Themes of Race, Class, and Education

Beneath the intimate, character-driven story of Dan and Drey lies a broader commentary on the American education system, race, and class. Set in an inner-city school, Half Nelson paints a grim picture of the challenges faced by both teachers and students in underfunded, overburdened schools. Dan’s lessons, while unorthodox, reflect a deep awareness of systemic inequality. He teaches history through the lens of social movements, often engaging his students in discussions about power, oppression, and resistance. His attempts to engage his students in critical thinking stand in stark contrast to the struggles they face outside the classroom—poverty, violence, and limited opportunities.

Race plays a significant role in the film, not as an overt theme but as a constant, underlying presence. Dan is a white teacher in a predominantly Black and Latino school, and the dynamics of this racial divide are ever-present but never explicitly addressed. Instead, they manifest in subtle ways—through Dan’s interactions with his students, his relationship with Drey, and his position as a white man struggling with addiction in a community where the consequences of drug use are often much more severe for people of color. The film doesn’t offer easy answers to these issues; instead, it presents them as part of the complex social fabric that both Dan and Drey must navigate.

The portrayal of the education system itself is bleak but realistic. Dan’s passion for teaching is evident, yet it is clear that the system he works within is failing both him and his students. His personal struggles are, in many ways, a reflection of the broader societal failures that leave both teachers and students in inner-city schools without adequate support. The film doesn’t idealize the role of the teacher as a savior but instead shows the limitations of what one person can do within a broken system.

A New Direction in Indie Cinema

Half Nelson was a breath of fresh air for indie cinema when it was released, offering a raw, unvarnished portrayal of addiction and inner-city life that felt miles away from the polished narratives of mainstream Hollywood. The film’s quiet, introspective tone, combined with its refusal to offer neat resolutions, marked it as a standout in a sea of formulaic dramas. At a time when addiction was often portrayed as a glamorous or melodramatic affliction in film, Half Nelson broke from this mold, presenting addiction as something far more insidious and mundane.

Gosling’s performance, in particular, was widely hailed as a turning point in his career. Up until this film, he had been known primarily for his roles in romantic dramas and mainstream fare. But Half Nelson showcased his ability to delve into the darker, more complex aspects of human nature. His portrayal of Dan Dunne is a masterclass in restraint, avoiding the histrionics that often accompany portrayals of addiction in favor of a more nuanced, internalized performance. The result is a character who is both sympathetic and deeply flawed, someone who is trying to do good in the world but is constantly undermined by his own worst impulses.

The Legacy of Half Nelson

Nearly two decades after its release, Half Nelson remains a powerful study in character development and moral ambiguity. The film’s exploration of addiction, race, and education is as relevant today as it was in 2006, offering a sobering look at the personal and systemic struggles that continue to shape American life. While the film does not offer easy answers, it provides a deeply human portrayal of people trying—and often failing—to navigate their way through a world that is indifferent to their suffering.

Dan Dunne is not a hero in the traditional sense, nor is he a villain. He is, instead, a profoundly human character, one whose struggles and flaws make him all the more relatable. In Half Nelson, we are reminded that redemption is not always a linear process, and that sometimes, the best we can hope for is a moment of connection—a brief respite from the chaos that surrounds us.

In the end, Half Nelson leaves us with more questions than answers, but that is precisely what makes it such an enduring and powerful film. It challenges us to confront the messy, often contradictory nature of the human experience, and in doing so, it offers a kind of quiet, bittersweet hope: that even in our darkest moments, there is the possibility of connection, understanding, and, perhaps, redemption.